Imagine trekking through the icy peaks of the Himalayas. The wind is howling. The snow? Stretches as far as the eye can see, untouched… well, except for some strange footprints.

Over the centuries, explorers, adventurers, cryptozoologists, and scientists have ventured into this wild, frozen landscape. Their mission? To find one of the world’s most legendary creatures: the Yeti.

And let me tell you, some of these Yeti expeditions found way more than they bargained for.

Curious? You should be. The real question is: What did they actually find?

In this article:

B. H. Hodgson (1832)

In 1832, Brian Houghton Hodgson (a British naturalist stationed in Nepal) led one of the earliest Western expeditions into the Himalayas that recorded an encounter with a strange animal.

But here’s the twist—Hodgson himself didn’t see it. His Sherpa guides did. According to them, this creature was large, hairy, and walking on two legs. It was hiding behind trees in a heavily forested area at high altitudes. And it quickly fled when it realized it had been seen.

Basing his observations on the limited zoological knowledge of the time, Hodgson thought that his Sherpas had likely seen an orangutan.

However, that was an odd conclusion. How so? Orangutans are not native to mainland Asia. They are typically native to the Southeast Asian islands of Borneo and Sumatra.

Hodgson was a naturalist. He was also familiar with the local fauna. He should have known that there were no orangutans in the region. So why document the strange sighting this way?

Nonetheless, Hodgson wrote about the encounter in a report for the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. It was the first known Western publication to mention a Yeti-like creature. And the reason for many Yeti expeditions over the following years.

William Hugh Knight Sighting (1888)

In 1888 (more than 50 years after Hodgson’s sighting), the British explorer William Hugh Knight recorded another potential Yeti sighting. This time, during an expedition in Tibet.

Knight was traveling through a remote region close to Mount Kangchenjunga (the third-highest mountain in the world). Here, locals were already convinced of the existence of strange bipedal creatures hiding in caves in the mountains.

So, what exactly happened? Well, according to Knight, while walking along a mountain trail, he saw something… different. A 6-foot-tall creature—covered in matted hair—walking on two legs. That’s right, upright—like a human but clearly not one.

Knight claimed that what he saw was clearly not a bear. Or any other known animal. He strongly believed he saw something truly unusual.

Though he didn’t manage to collect any physical evidence, Knight’s vivid description got people thinking. Could there really be an undiscovered species living high up in the Himalayas?

British Mount Everest Expedition (1921)

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Howard-Bury’s expedition marked the first extended exploration of the north face of Mount Everest. While not a Yeti expedition per se, the group definitely encountered something weird.

On September 22, 1921, while mapping out possible summit routes, Howard-Bury’s team spotted footprints near Lhakpa La pass at about 21,000 feet. The unusual part? The prints were about three times the size of a human’s.

When they noticed the footprints, Howard-Bury’s Sherpas started to yell, “Meh-Teh! Meh-Teh!” (the local name for the Yeti).

But Howard-Bury wasn’t convinced. He thought the tracks belonged to a gray wolf and blamed the melting snow for making them seem larger.

Related: Mapinguari Sightings: Is a Real-Life Monster Hiding in the Amazon?

Sounds reasonable, right? Well, here’s the catch—there were no known wolves (gray or otherwise) in the Himalayas at the time. Likely, Howard-Bury wasn’t aware of this fact.

Nevertheless, this uncertainty made the whole incident even more attractive to the Western press. Which immediately jumped at the chance to report on the discovery, quickly spinning Howard-Bury’s story into something larger—claiming it as the first Yeti expedition.

The truth? His journey wasn’t intended to search for any creatures. Undiscovered or otherwise. But you know how it goes—the media had found a juicy story, and who can argue with the headlines once they start rolling?

N. A. Tombazi (1925)

In 1925, N. A. Tombazi (a Greek photographer working with the Royal Geographical Society) went on an expedition to the Zemu Glacier near Kangchenjunga. And yes, he saw something strange.

At around 15,000 feet, Tombazi spotted a tall creature walking upright in the distance. It paused now and then, pulling at some low-lying rhododendron bushes.

Tombazi observed its behavior for about a minute from around 200 to 300 yards. He wasn’t, however, able to take any photos.

Later, his team found footprints—six to seven inches long and four inches wide. Smaller than those found in other expeditions, but still definitely bipedal.

SpookySight recommends:

- 8 Astonishing Yeti Myths You Probably Haven’t Heard Of

- Mongolian Death Worm: Fact or Fiction? Inside the Gobi Desert’s Greatest Mystery

- Top 10 Most Mysterious African Cryptids You Need to Know About

Another thing Tombazi noticed was how similar the footprints were to human tracks (like the ones his own group left behind). But he also noted subtle differences, which he couldn’t explain.

For instance, how widely spaced the toes were compared to human footprints. That aspect suggests a more primitive (or unusual) foot structure.

It’s noteworthy here that Tombazi never claimed to have seen a Yeti. But his story appeared in the Royal Geographical Society’s journal shortly after his return in 1925. And it was bizarre enough to draw some attention in the scientific circles.

Bill Tilman (1937)

This 1937 expedition was part of his more general exploration of the Himalayas and followed Tilman’s groundbreaking first ascent of Nanda Devi in 1936.

The Tilman expedition wasn’t really a Yeti expedition. It was more of a reconnaissance one. What he didn’t expect to find? Another set of mysterious footprints.

So what exactly happened? While the group was exploring high-altitude areas around Nanda Devi Sanctuary (which at the time had rarely been visited by outsiders), they came across 8-inch-long footprints in the snow.

Given the reports from the previous expeditions, unidentified footprints wouldn’t make any headlines anymore. The only difference? The fact that they were found in such a remote, untouched area. Far away from usual trails, camps, or human settlements.

Eric Shipton (1951)

Another Yeti expedition happened in 1951. Well, it’s not exactly a Yeti expedition. However, what they found is closely related to our topic at hand.

While scouting new climbing routes near Mount Everest, British mountaineer Eric Shipton stumbled upon something unexpected—large footprints along the Menlung Glacier, at nearly 20,000 feet. The tracks were very similar to the ones reported by previous expeditions.

The team quickly documented their findings. And Shipton famously took photographs of the prints, using an ice axe placed next to them for scale.

Unlike earlier, vague accounts of Yeti sightings, these photos offered the first clear visual evidence that something unusual had left its mark in the high Himalayas.

Daily Mail Yeti Expedition (1954)

1954 is the year of the first official Yeti expedition. Led by Ralph Izzard, the Daily Mail Yeti Expedition was the first attempt to scientifically investigate the Yeti legend.

The mission lasted four months—from February to May 1954. And involved a large team of nine explorers and nearly 300 porters. Their primary goal was to gather physical evidence of the Yeti’s existence, focusing their efforts around the Everest region (and particularly on the Pangboche Monastery).

Why here? Because there were rumors that the monks had some invaluable Yeti artifacts in their possession.

Believe it or not, the rumors were true. The team found the monastery, gained access inside, and the monks showed them the now famous Pangboche Yeti scalp.

It was a shocking discovery. This was the first physical evidence that the Yeti was not just a local legend. Everyone was ecstatic.

But that didn’t last long. The hair and skin samples collected from the scalp were sent to London for further analysis. Professor Frederic Wood Jones (a leading expert in comparative anatomy) was in charge of doing so.

However, he later figured out that the hairs did not come from some undiscovered species. But instead, from a coarse-haired hoofed animal, possibly a serow.

Despite its relative unsuccess, the Daily Mail laboriously publicized its Yeti expedition. The tabloid published numerous sensational articles before, during, and after the team’s journey.

The first major article about the scalp was published on March 19, 1954, sparking widespread public interest.

Tom Slick (1956-1957)

Between 1956 and 1957, Tom Slick organized some of the most ambitious Yeti expeditions (and the first privately financed) to date. Tom Slick, a Texas oil tycoon with a huge passion for cryptozoology, funded several tours to Nepal and the Himalayas specifically to search for evidence of the elusive cryptid.

Because of the generous budget, the team was well-equipped. It included naturalists, professional trackers, expert climbers, and Sherpas who knew the terrain.

The 1956 expedition was relatively successful. The group discovered a set of footprints very similar to the ones found by Eric Shipton a few years earlier. The prints were clearly bipedal, large, and located in high-altitude, remote areas, far from where typical human or animal activity would be expected.

The team also collected fecal samples, which were believed to belong to the Yeti. Analysis of these samples reportedly found unknown parasites, which cryptozoologists took as a sign that the host—potentially the Yeti—was also an unknown species.

While the finding was indeed interesting, Slick was disappointed. He was hoping for something more.

In 1957, the oil magnate funded another expedition. This time, the goal was all about finding physical evidence. And they did. Or at least that’s what they thought.

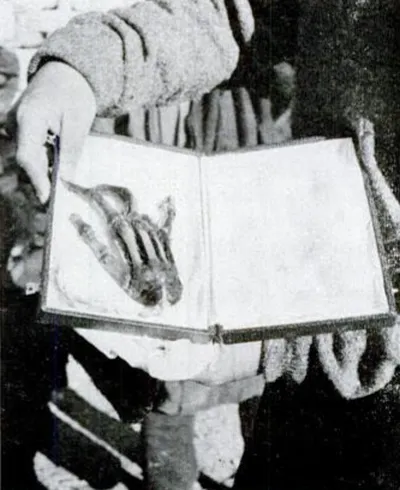

While talking to locals, Slick heard rumors about the Pangboche Monastery in Nepal, where monks claimed to have a Yeti hand—a sacred artifact believed to belong to the mythical creature. The hand had been worshipped for centuries, with the monks viewing it as a holy relic that protected the monastery.

Intrigued by the story, the team made their way to Pangboche.

The monks were initially open to showing the hand. They believed Slick and his companions were honorable men.

We can only imagine Slick’s surprise when he first saw the mummified hand. In his notes, he described it as an extraordinary find. The hand was held together by skin and bone and appeared much larger than a normal human hand.

Convinced that was the proof they were looking for, the team asked the monks if they could take the hand for scientific testing. The monks, however, refused. They became agitated, claiming that removing the hand would bring disaster to the monastery.

So, what did Slick do? He devised a plan to steal a piece of the hand. He sent his associate (Peter Byrne) back to the monastery with clear instructions to do whatever was necessary to obtain a part of the hand.

Once inside, Byrne convinced the monks to let him inspect the artifact one more time. He reportedly waited until they were distracted or sleeping before cutting off a finger from the hand, replacing it with a human finger so the monks wouldn’t notice the theft.

After obtaining the finger, Byrne needed to get it out of Nepal. Slick called on his friend, actor James Stewart, who was vacationing in India with his wife. Stewart helped smuggle the Yeti finger out of the country by hiding it in his wife’s… lingerie case.

Once in London, the finger was handed over for examination by the experts at the Hunterian Museum (a part of the Royal College of Surgeons).

Once again, Professor Frederic Wood Jones was responsible for finding the finger’s origins. As per usual, Wood Jones was thorough in his approach. However, he had to work with the limited technology available at the time (keep in mind that DNA testing wasn’t a thing yet).

He concluded that the finger was human. Which was disappointing for many.

It wasn’t until 2011 when a team at Edinburgh University performed DNA testing on samples from the finger. Their definitive conclusion? The mitochondrial DNA proved that the Pangboche finger was 100% human.

Peter Byrne (1959)

In 1959, Peter Byrne (yes, the guy who stole the Pangboche finger) organized another expedition in the area. He was looking for more artifacts or potential proof of the cryptid’s existence.

Byrne found the artifact he hoped for at the Khumjung Monastery: another alleged Yeti scalp. It was one of several presumably Yeti scalps discovered in monasteries across the region, including the infamous Pangboche and Namche Bazaar scalps (see above).

Much like the other scalps, this one, too, was considered a relic by the local community. But here’s the thing. The monks at the Khumjung Monastery were far more open to having their precious relic examined… for “a substantial donation for the upkeep of the temple.”

Excited that he may have finally found the underlying proof, Byrne and his team collected hair and skin samples from the scalp and took them back to London for further study.

However, after the samples were examined, the results were clear: the hairs belonged to a known animal, likely the Nepalese serow.

Sir Edmund Hillary’s Silver Hut Expedition (1960-1961)

The 1960-1961 Silver Hut Expedition (led by Sir Edmund Hillary) was a significant and well-publicized effort, blending scientific research, high-altitude mountaineering, and a search for the Yeti. It’s probably one of the best-known Yeti expeditions to date.

Hillary was looking to test human endurance at extreme altitudes. The team even attempted to summit Makalu without oxygen. They also performed extensive physiological research in a specially designed Silver Hut at 19,000 feet in the Himalayas.

Hillary also set out to examine the alleged evidence of the Abominable Snowman in the region. His team traveled through areas known for Yeti sightings, including the Rolwaling Valley. They purchased several alleged Yeti artifacts, including a Yeti scalp.

Interestingly, Hillary was the first to convince the monks to outright give him the scalp. In exchange for the artifact, he promises to support the local Sherpa community, including the construction of a school.

Along with the scalp, other relics, such as goat skins and animal bones, were examined. These relics were later transported to Europe and the United States for scientific testing.

After careful expert analysis, the scalp was determined to be made from the skin of a serow.

Reinhold Messner (1970)

In 1970, the mountaineer Reinhold Messner attempted to climb Nanga Parbat in Pakistan.

Here’s where he reportedly had his first encounter with what he believed to be a Yeti—a large, hairy creature with big eyes and teeth. Messner was not a believer. But his views changed after the alleged encounter.

Messner spent the next 14 years searching for more evidence of the Yeti. Eventually, in his 1998 book My Quest for the Yeti, Messner concluded that what he had seen was likely a Tibetan blue bear or a large, upright-walking bear native to the region rather than an unknown species.

Joshua Gates (2007)

In 2007, TV host and adventurer Joshua Gates was on a Yeti expedition filming an episode for the television show Destination Truth.

During their exploration, the team found a set of giant 13-inch-long footprints in the snow near the Manang village. Gates immediately asked for the prints to be put in plaster casts and returned home for further analysis.

The results weren’t the ones Gates expected. Opinions were divided. Some scientists argued the footprints could have been from a known animal, while others believed they were too distinct to be from a common species.

Indian Army Yeti Sighting (2019)

In April 2019, the Indian Army claimed to have found Yeti footprints near the Makalu Base Camp in the Himalayas, located near the border between Nepal and China.

The army’s mountaineering expedition team discovered footprints measuring 32 inches long and 15 inches wide. Huge. Much larger than any of the previously discovered ones.

The discovery was publicized through the Indian Army’s official Twitter account, which included photos of the tracks. But despite the publicity, no additional evidence surfaced to support the claim, and the Yeti mystery remained unsolved.

SpookySight’s Take

In the end, what did these Yeti expeditions really uncover? While the excitement surrounding the Yeti has lasted for over a century, the physical evidence has consistently fallen short.

The Pangboche hand and the various Yeti scalps, once hailed as proof of the creature’s existence, were ultimately revealed to be fakes—most likely crafted from the hides of local animals like the serow.

It’s hard not to wonder if some of the monks capitalized on the Yeti frenzy by showcasing these relics to eager Western explorers.

And what about the footprints? In many cases, it was the local Sherpas who discovered the tracks or claimed to have seen the creature. Not the Westerners themselves.

Could the footprints have been planted to fuel interest in the legend—or even to attract more expeditions, tourism, and funding to these remote areas?

While some of these Yeti expeditions resulted in sensational stories, they’ve left us with more questions than answers. Was the Yeti ever real, or were these expeditions chasing shadows in the snow? What role did local beliefs—or opportunism—play in shaping the evidence?