In the dense jungles of Guatemala, a discovery both haunting and historically significant has been brought to light. Hidden within an elaborately crafted Maya altar, the remains of what appear to be sacrificed children have been unearthed—revealing more than just bones. They tell a story of political turmoil, cultural collision, and the shadows of a mighty civilization’s reach.

The unearthed altar, striking in its craftsmanship and mysterious in its intent, has captivated archaeologists not because of its colorful panels or its elaborate design, but because of what was found inside: the bones of a child believed to have been ceremonially killed. This discovery, detailed in a newly published study in the journal Antiquity on April 8, is being seen as a profound window into the violent power dynamics that once shook the ancient Maya city-state of Tikal.

A Shrine From a Time of Upheaval

It is believed that the altar was constructed during the latter part of the 4th century CE, situated deep within the once-glorious Maya kingdom of Tikal. This sacred structure stands as a silent witness to an era marked by conflict and shifting political tides.

Decorative panels, painted in vibrant shades of red, black, and yellow, adorn the altar. These panels depict a figure adorned with a feathered headdress, standing near what appears to be royal emblems and shields. The facial features—marked by almond-shaped eyes, a prominent nose bar, and doubled earspools—evoke images reminiscent of the Maya deity commonly referred to as the “Storm God.”

Experts have attributed the altar’s fine artistry to an unknown but highly trained artisan, likely influenced by or originating from Teotihuacan—a powerful ancient metropolis located approximately 630 miles to the west, near present-day Mexico City. The artist’s skill, as well as the visual elements depicted, suggest that the altar’s creation was not merely decorative, but also deeply symbolic.

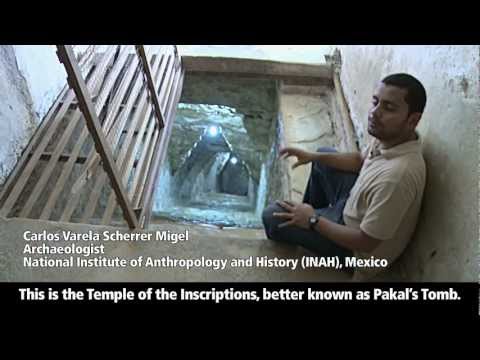

“This discovery solidifies what has long been suspected—that this was an especially volatile and transformative period for Tikal,” noted Stephen Houston, one of the co-authors of the study and a professor of archaeology at Brown University. According to Houston, the altar presents compelling proof that elites from Teotihuacan had journeyed into Tikal, bringing with them not only their customs but also the architectural and ritual designs from their homeland.

Read more: Archaeologists Find an Ancient Temple Hidden in the Heart of a Cliff

Rival Cities: Tikal and Teotihuacan

The city of Tikal, founded as early as 850 BCE, began as a modest settlement with limited influence. But by 100 CE, it had transformed into a flourishing kingdom—its influence echoing throughout the Maya region. Enormous temples and ceremonial complexes still rise above the jungle canopy today, silent guardians of a once-mighty civilization. Over time, Tikal found itself locked in fierce rivalry with the Kaanul dynasty, as both powers vied for dominance over the broader Maya world.

Teotihuacan, often referred to as “the city of the gods,” was a vast urban center whose grandeur rivaled the world’s greatest cities during its peak between 100 BCE and 750 CE. Within its bounds resided more than 100,000 people, making it one of the largest population centers of its time. Home to massive pyramids, including the famed Temples of the Sun and Moon, the city stood as a marvel of architecture and power. Yet, by the time the Aztecs rose to prominence in the 14th century, Teotihuacan had long since been abandoned under still-debated circumstances.

Evidence suggests that regular contact between Tikal and Teotihuacan may have begun around 650 BCE. At first, these interactions likely involved simple exchanges of goods or ideas. But with time, tensions appear to have escalated.

“It’s as if Tikal caught the attention of a giant—and the consequences were profound,” said Houston. “What started as trade soon turned into something much more invasive.”

The Secrets Within the Altar

Clues to this growing tension were unearthed decades ago. In the 1960s, a carefully carved stone inscribed with glyphs was discovered. This monument described, in broad terms, a violent episode in 378 CE—when Teotihuacan forces arrived and dismantled the ruling power of Tikal. The record described a regime change in which the king was forcibly removed and replaced by a puppet ruler loyal to Teotihuacan.

The notion of a politically motivated coup, supported by foreign intervention, was further reinforced when researchers utilizing LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology uncovered the remains of what appeared to be a miniaturized version of Teotihuacan’s citadel. Situated just outside the heart of Tikal, this replica had been concealed beneath mounds of earth—suggesting it was either intentionally buried or long forgotten.

The recently studied altar has now added another piece to this intricate historical puzzle. Believed to have been constructed during the same period as the coup, the altar has drawn attention not only for its artistic merit but for the tragic discoveries within.

Inside, archaeologists found the remains of a young child seated in a deliberate, ceremonial position. Though both the Maya and Teotihuacan cultures are known to have practiced human sacrifice, this particular burial style was virtually unheard of in Tikal. However, it aligns closely with ritual practices observed in Teotihuacan.

Additional skeletal remains—those of three more children, none older than four years—were located around three sides of the altar. According to Lorena Paiz, the lead archaeologist overseeing the discovery, these remains are further evidence that the altar served as a site for child sacrifice.

“These burials suggest ritual offerings,” Paiz explained in an interview. “And their placement around the altar supports the interpretation of a ceremonial purpose, likely tied to significant political or spiritual events.”

Even more intriguing was the presence of an adult’s body, found alongside a green obsidian dart point—an artifact unique to Teotihuacan culture and absent from typical Maya weaponry. The materials and craftsmanship of the weapon underscored the growing influence, or perhaps dominance, of Teotihuacan over this part of the Maya world.

What is particularly compelling is the fact that the altar and its surrounding structures were later buried and abandoned. For the Maya, structures were often entombed ceremoniously, only to be built over with new monuments. Yet in this case, the site was not repurposed. It was left untouched—as if those who lived later had chosen to distance themselves from it entirely.

“This wasn’t simply buried and forgotten,” stated Andrew Scherer, another co-author of the study. “It was treated with the same kind of caution as one might treat a place with bad memories—almost like a radioactive site. That speaks volumes about how the people of Tikal felt about this chapter in their history.”

Read more: Beautiful Relics From Ancient Egypt Were Found In Hidden Chamber Down A 14-Meter Shaft

The Weight of Memory and Power

While the takeover of Tikal by outsiders may have shaken the kingdom to its core, it was not without consequence. Paradoxically, the city grew more powerful in the aftermath. Over the next few centuries, Tikal would rise to an unprecedented level of influence, commanding authority across vast regions of the Maya world. However, like many great civilizations, its light would eventually dim. By the year 900 CE, Tikal—alongside much of the Maya world—fell into decline.

Despite this, a sense of wistful remembrance seemed to linger.

“There’s a strange kind of admiration in how the people of Tikal remembered that time,” said Houston. “Even as they later declined, they continued to think of that moment when they were swept into the orbit of Teotihuacan as something almost grand—something that shaped who they were.”

What becomes apparent from this tale is not simply a clash of two civilizations, but a reflection of a recurring pattern throughout human history: a dominant power reaching beyond its borders in pursuit of influence and wealth, leaving lasting impacts on the cultures it touched.

“It’s a story as old as civilization itself,” added Houston. “Teotihuacan saw the Maya lowlands not just as a neighbor, but as a treasure trove—a place rich in jade, exotic feathers, and prized cacao. To them, it was a land flowing with milk and honey. And so, they came.”

Featured image: Freepik.