In 1521, a terrifying case gripped the French town of Poligny. Three men were accused of morphing into bloodthirsty beasts, committing acts of cannibalism, and striking pacts with the Devil.

But how much of this story is actually true? What’s accurate (and documented), and what parts are a myth?

Join us as we try to uncover more about these bizarre historical accounts, separate fact from folklore, and explore the chilling legacy of the Werewolves of Poligny.

In this article:

Who Were the Infamous Werewolves of Poligny?

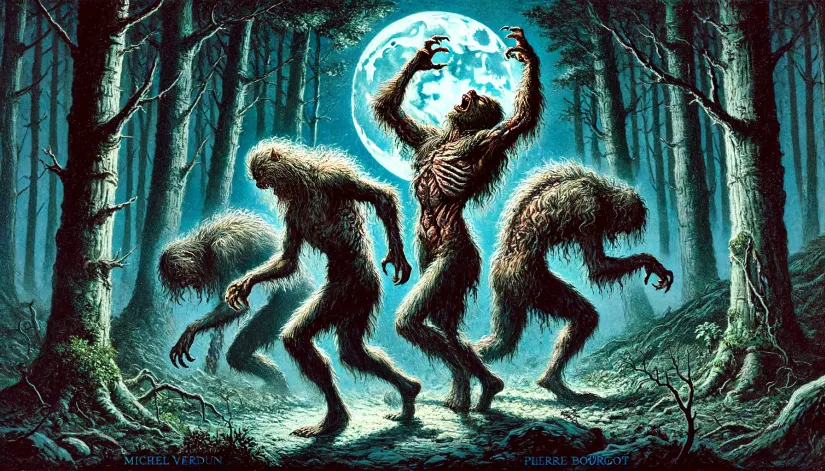

The Werewolves of Poligny were Philibert Montot, Pierre Bourgot, and Michel Verdun.

They were allegedly involved in a famous case of lycanthropy, cannibalism, and witchcraft in 1521 in Poligny, France.

The three men were judged by Maitre Jean Bodin (a prior at a Dominican convent in Poligny, France-Comté), found guilty, and executed by burning at a stake.

However, their tale remains one of European folklore’s most bizarre cases of alleged werewolves. And many still believe that there may be something more to the story.

So what exactly happened? And were the three men truly capable of metamorphosing into bloodthirsty beasts?

The Werewolves of Poligny

The Accusations

The accusations against the Werewolves of Poligny (Michel Verdun, Pierre Bourgot, and Philibert Montot) were multifaceted and deeply disturbing.

Historical references indicate a web of alleged crimes that included witchcraft, cannibalism, and the most chilling accusation of all—lycanthropy (the transformation into savage werewolves).

So here’s what we know:

It all started in 1521 when an unnamed traveler was attacked by an unusually large wolf. The man, however, was able to defend himself and somehow managed to injure the beast.

He then tracked the wounded animal to Michel Verdun’s house, where he allegedly found Verdun injured, dripping blood, and his wife helping him. Naturally, the traveler became highly suspicious and reported the incident to the authorities.

The local authorities got involved pretty quickly. And, as you may expect, the odd discovery—Verdun’s arm was torn apart—prompted some questions about his involvement in the attack.

The traveler was also questioned. He claimed that the deep wound on Verdun’s arm was similar to the wound he inflicted on the beast. And, indeed, the man covered in blood was the wounded beast he chased away.

Ultimately, this testimony set in motion the events that would eventually lead to the trial and execution of Verdun (along with two of his close friends—Pierre Bourgot and Philibert Montot).

The Trial

The trial of the Werewolves of Poligny, presided over by Maitre Jean Bodin, stands out as a notable event in the annals of witchcraft and lycanthropy trials in early modern Europe.

The specifics of the trial (while not fully detailed in historical records) suggest that Michel Verdun was subjected to a trial by ordeal—a method deeply rooted in the judicial practices of the time for dealing with accusations of witchcraft and lycanthropy.

Trial by ordeal was a deeply ingrained belief system that posited divine intervention as the ultimate judge of a person’s guilt or innocence.

In cases of lycanthropy—where individuals were accused of transforming into wolves or engaging in witchcraft—the ordeal could take various forms. Each designed to uncover some supernatural evidence of guilt.

For Verdun, the ordeal likely centered around identifying physical markers, which are typically believed to indicate that the person who has them can transform into a wolf.

One common test during such a trial was the meticulous examination of the accused’s body for signs considered unnatural or indicative of a pact with the Devil—such as excessive body hair or unusual markings.

These markings were considered the Devil’s brand, a sign of the accused’s allegiance to malevolent forces and a physical manifestation of their ability to transform into a wolf.

The search for such signs was typically conducted with the belief that these physical anomalies were incontrovertible evidence of lycanthropy, as normal humans were not expected to bear such marks.

Furthermore, the trial by ordeal for lycanthropy accusations might have extended to more torturous methods (designed both to elicit confessions and to reveal any hidden signs of witchcraft or lycanthropy).

This could include some forms of physical pain.

Back then, the widely spread assumption was that a witch (or werewolf) would easily endure more pain than an average human. Or that extreme duress would somehow force them to reveal their true nature.

Confessions and Convictions

Since there is little reliable information about the actual trial, we had to dig deep to find out more.

One of the few reliable sources we could find is Summers Montague’s “The Werewolf“ (London, 1933. Reprint, New York: University Books, 1966).

Here’s what we discovered:

Historical accounts depict Michel Verdun confessing to attacking and devouring children while in werewolf form.

According to records, Verdun confessed under torture to being a werewolf and implicated Bourgot and Montot in similar activities.

Both Bourgot and Montot were swiftly apprehended and subjected to similar forms of torture and coercion to force confessions from them.

So, did they corroborate Verdun’s statements?

Well, yes and no. According to Montague, Bourgot ‘admitted’ to making a pact with three mysterious men dressed in black. One of them offered him great powers in exchange for his soul:

[…] 19 years earlier, Bourgot had been collecting his flock of sheep during a great thunderstorm, when he was accosted by three demon horsemen, clad in black. One of these demons asked what troubled him, to which Burgot replied that he was afraid that his sheep might be attacked by wild beasts. The demon told him that if he would serve him as master and renounce God, Our Lady, the company of Heaven, and his baptism, all his sheep would be safe. He would also have money.

Burgot acknowledged the demon. Later, in company with Michel Verdun, he attended a Sabbat of warlocks, where he stripped naked and was anointed with an unguent, after which his limbs became hairy and his feet like those of a beast. Verdun also changed his form, and they both ran like the wind. In the shape of wolves they pursued and attacked children and committed other hideous crimes.

After the pact was sealed, Bourgot claimed he became increasingly unable to control his animalistic urges and slowly turned into a mindless beast.

This transformation from man to wolf ultimately led him to commit a series of heinous crimes, including the killing of children.

Montot, on the other hand, didn’t admit to anything.

The Burning Pyre: A Grisly Spectacle

Found guilty, the unfortunate trio met a gruesome end. In 1521, Michel Verdun, Pierre Bourgot, and Philibert Montot were executed by burning at the stake—a common punishment for witchcraft and crimes linked to the Devil.

Were the Werewolves of Poligny Real Werewolves?

The Werewolves of Poligny—Michel Verdun, Pierre Bourgot, and Philibert Montot—were not actual werewolves in the literal sense.

The lycanthropy accusations and the subsequent trials were likely based on superstitions and fears prevalent during that era.

Michel Verdun confessed under torture to being a werewolf and implicated Bourgot and Montot in similar activities.

Bourgot also confessed to being a shapeshifter and admitted to committing heinous crimes like murder and cannibalism.

However, there is little doubt that these confessions were coerced through torture (or threats of torture), casting doubt on the authenticity of the claims of lycanthropy and supernatural transformations.

In fact, several other werewolf cases from history bear similarities to those of the Werewolves of Poligny.

The Werewolf of Chalons (also known as the Demon Tailor), the Wolf of Ansbach, Thiess of Kaltenbrun, Peter Stumpp, Jacques Roulet, and Gilles Garnier… all these cases highlight the widespread nature of lycanthropy accusations across Europe during the medieval and early modern periods.

So, was there a common unknown link? Maybe something supernatural? Perhaps there is some truth in their bizarre stories?

Well, rather than a supernatural link, the commonalities between these cases more likely reflect a human tendency to explain unexplainable tragedies and fears through the lens of the supernatural.

It’s a complex process that often involves singling out individuals who deviate from social norms or are convenient scapegoats, attributing supernatural abilities or pacts with the Devil and using them to explain societal ills or misfortunes.